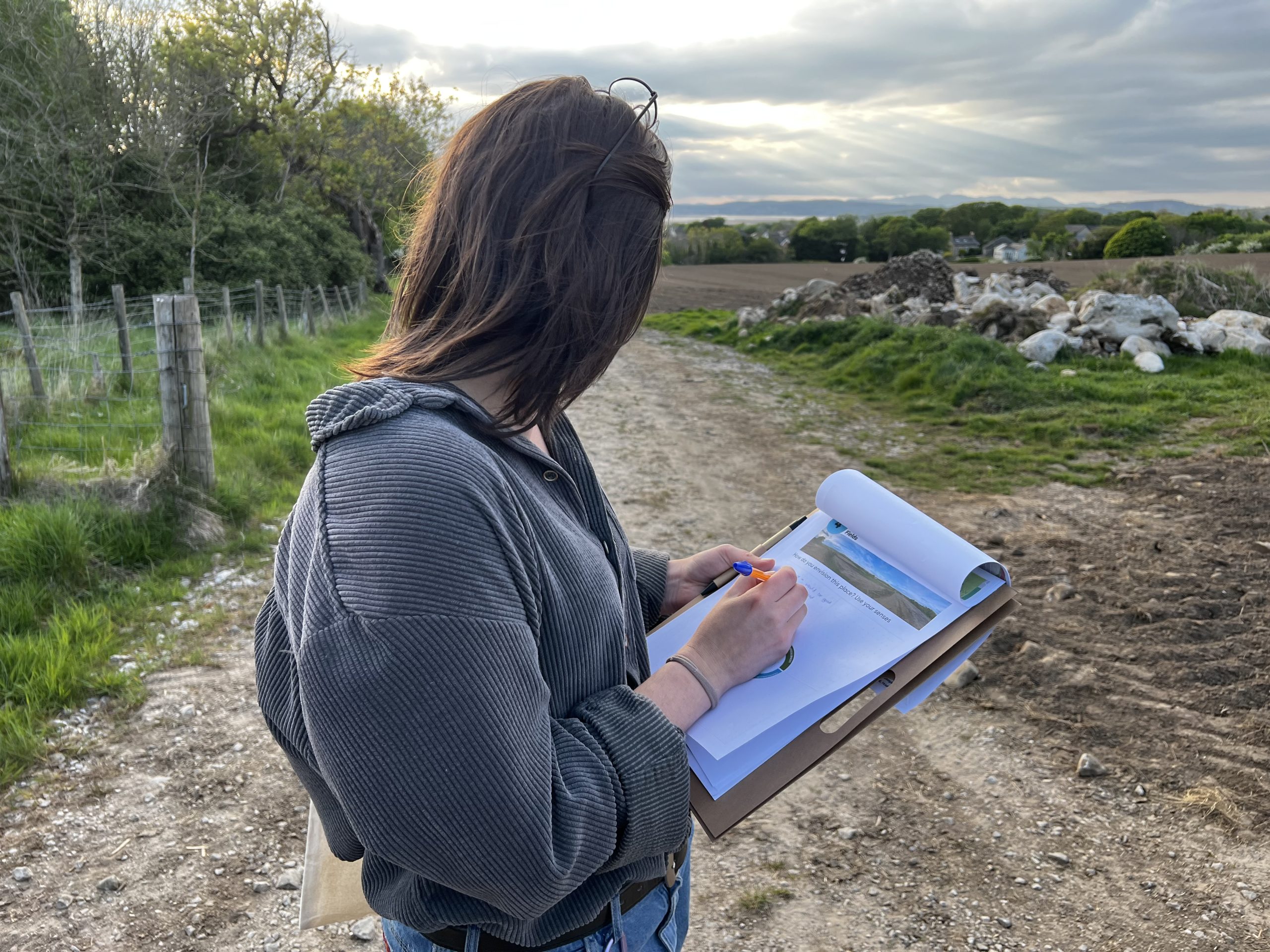

Standing on a hill behind Carnforth, looking out over Morecambe Bay towards the Lake District peaks, our group of young adults and policymakers found ourselves asking, “What if the things that seem like planning challenges are actually opportunities in disguise?”

The view before us captured exactly what we’d been discussing: a town with real assets like the canal, the railway heritage, and stunning natural surroundings, where creative thinking could turn apparent limitations into pathways for something different.

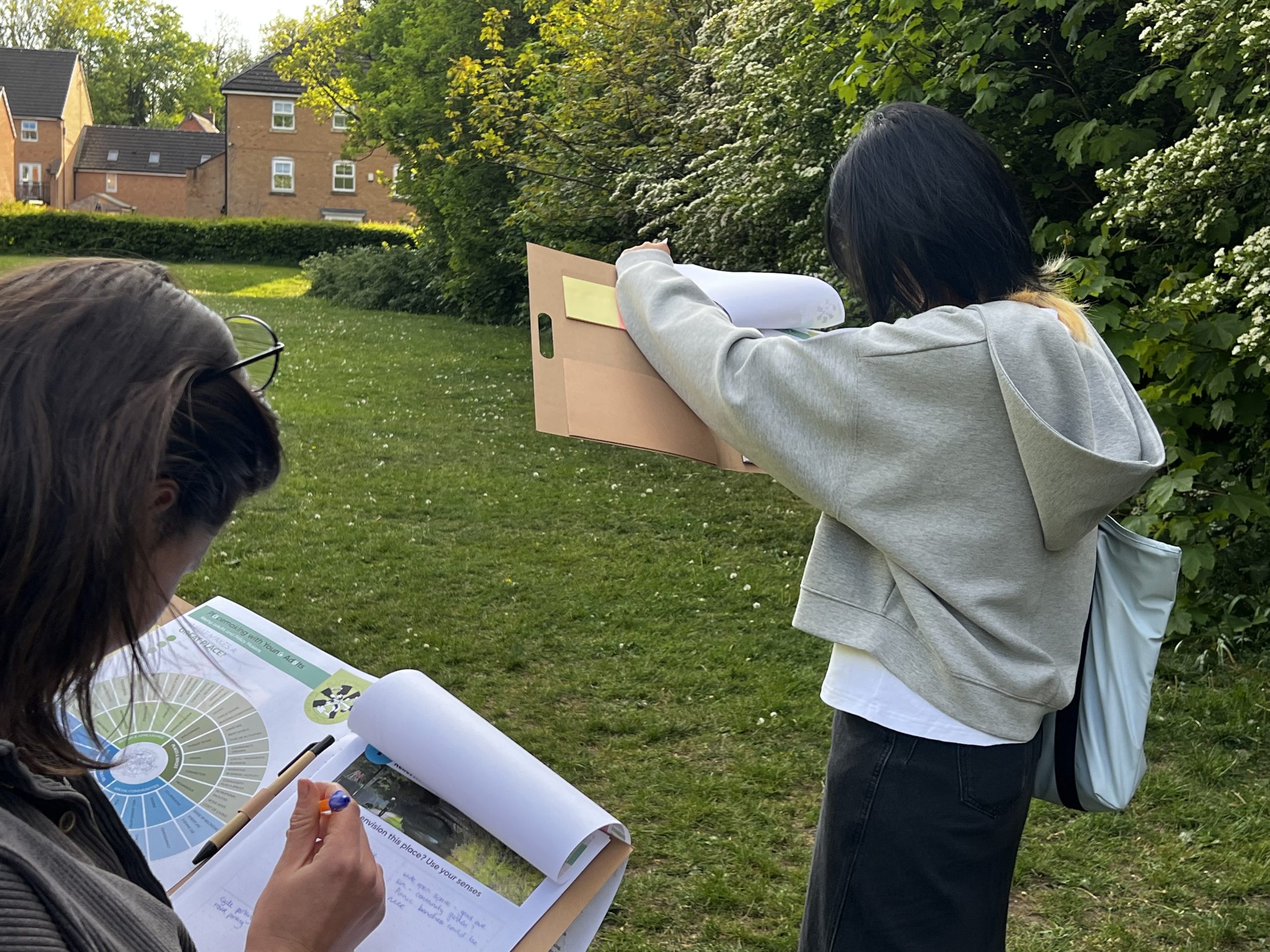

This was the first of three walks as part of the Placemaking with Young Adults project, hosted by Lancaster University in collaboration with Lancaster City Council. The project aims to bring young people meaningfully into conversations about the future of the place we call home, while also testing new forms of democratic innovation through more participatory planning. By linking local voices to the Local Plan process, it explores how inclusive placemaking can address challenges such as climate change, social equity, and sustainable development.

The decisions made now will shape our lives for the next 10–15 years, a timeline that feels particularly urgent when you consider that many of us who were there on the day will be building careers and building community during this time, all while navigating the housing crisis, the cost of living, and the effects of climate change.

Reimagining Lancaster Canal

One conversation that particularly stuck with me centred on the brownfield site opposite the Canal Turn pub. As someone who has lived on the Lancaster Canal for a couple of years, I have often noticed its sunny, south-facing position and thought it would be a lovely spot to sit, though I never knew what it was or how I would get there.

Earlier in the walk, we had discussed the lack of benches, picnic tables and community infrastructure in the green spaces we passed. Despite these green spaces being community assets, they felt unwelcoming as there was nothing indicating we were meant to be there. This sense that public spaces weren’t truly public had only intensified in recent years, making the question of how to ensure community assets feel genuinely welcoming a central theme of our conversation.

The canal itself has enormous potential for promoting community, sustainable living and biodiversity. It could serve as a natural gathering point for people of all ages, and providing facilities for boaters would address real needs, as many of us are feeling the impacts of funding cuts and climate-related challenges. Creating spaces where boaters and local residents can come together would strengthen connections across different ways of living, while also drawing visitors into Carnforth. When positioned alongside the town’s other attractions, such as the railway, the canal could contribute meaningfully to the local economy and help establish Carnforth as a destination where culture, community and the natural environment meet.

Living alongside the canal also offers a unique way of experiencing nature, with the changing seasons visible week by week. With its towpath already established as active travel infrastructure, the canal combines heritage protection with opportunities for walking and cycling, while safeguarding biodiversity. Its potential to support healthier, more sustainable living feels unmistakable.

Approaching Constraints as Opportunities

Circling back to the brownfield site, we discussed potential ideas for development in the area. One of the planners explained that it might be unsuitable for housing because the existing infrastructure could not cope with the added traffic. Rather than treating reduced car access as a barrier, we questioned the assumption that every resident would want to own a car, or that housing must always be designed around that expectation. Given trends showing young people are driving less, this constraint could actually be an opportunity to think differently about housing.

Ideas began to flow naturally from this reframing. We talked about transforming the site into a community square with cafés and small shops, designed alongside facilities for boaters as a way of protecting and celebrating the area’s heritage. We also emphasised the importance of incorporating green and blue spaces, recognising that the site’s past as a cement works has given way to its present as a habitat where deer and otters have been spotted; a reminder of how resilient nature can be and how vital it is to protect biodiversity in future plans.

What struck me most was how quickly our thinking shifted once we began viewing constraints not as barriers but as prompts for reimagining. It demonstrated that there is no one-size-fits-all vision of housing. While some people may prefer dedicated parking and suburbs, others value a more pedestrianised, community-focussed space. In this way, what initially appeared as a constraint actually opened the door to more creative and people-centred solutions.

For example: “You could be in a lot of new estates, and you could be in York, you could be in Lincoln, you could be anywhere because they’re the same houses.” This observation from one participant highlighted exactly what the walkshop was pushing against – the tendency for development to ignore local character and community needs. By bringing together voices that don’t typically shape planning decisions, the project revealed a real appetite for place-specific solutions and alternative provisions.

Collaborative Conversations

I came away with a genuine sense that the planners were interested in what we had to say. We explored challenges and possibilities together, with discussions about infrastructure limits or green space protection flowing seamlessly into conversations about opportunities.

What stood out most was how valued I felt throughout the process. Being able to share reflections on the impacts of lockdown and the lack of community infrastructure showed me that lived experiences could genuinely shape better environments. That recognition encouraged me to speak more openly and creatively, creating a dynamic where collaboration fostered trust and led to solutions that were both imaginative and grounded in people’s real needs.

“I think it’s about caring about the public space and the understanding of the relevance of it for cohesion and community resilience.” This participant’s reflection captures why the walkshop felt significant beyond just discussing one brownfield site. The process itself demonstrated how bringing community voices into planning conversations can shift focus from purely technical considerations to the social infrastructure that actually holds places together.

Author: Megan Pickles